Exhibition

In memory of a great artist and a legend of post-war Russian art

Oscar Rabin became a legend during his lifetime. Reporters interviewed him, film producers made — and will make still more — documentaries, and authors wrote — and still are writing more — books about him. The last years of his life had this special halo of universal recognition. The artist died in Italy on November 7, on the eve of the opening of his exhibition. A fitting end of an era and a fitting departure of a genuine artist: passing away in Florence — the city of art and artists — not for a day resting from his creative toils, renowned, loved

Not a single monograph or article discussing the development of art in Russia in the second half of the 20th century is complete without mentioning the Lianozovo Group, the leader of which was Oscar Rabin. The same is true for the notorious Bulldozer Exhibition, which the artist helped organize.

Today, everyone who knew him personally as well as all other admirers of his talent stand together in mourning, united by the significance of his figure. In the postwar Russian art, Rabin is a pioneer both in painting and in asserting the special position of a socially responsible artist, firm in his convictions, ready to defend them courageously and calmly, walking on the edge and being aware of the risks.

September 20, 1975. An exhibition at the VDNKh Culture Center is about to open. Oscar Rabin urges fellow artists to boycott the exhibition and demand to put the banned paintings back on display

Oscar Rabin’s biography is rich in events, intertwining his personal dramas with the public ones and the official history of Russia with an unofficial one. The title of his memoir that Rabin wrote in Paris, The Three Lives, is not accidental. Each of these lives is both a stage of his biography and a milestone in the history of the 20th century Russia. In 2008, just before the opening of his first retrospective in Russia, Oscar Rabin said —

…After the death of Stalin, my second life began, and in this second life I was able to express and realize myself as an artist, without pretending…

«The first life lasted from my birth to Stalin’s death, since both my life and the lives of all people in the Soviet land depended on this tyrant. Of course, as long as he was alive, I couldn’t become an artist, since the abilities that God gave me had nothing to do with culture and art the Stalin way. After the death of Stalin, my second life began, and in this second life I was able to express and realize myself as an artist, without pretending, without faking the state-approved art. I wouldn’t have succeeded in faking it anyway, because I can’t draw in any other way than I do. This life lasted until 1978, when I found myself an unwitting emigre in Paris, being already an established artist with my own worldview and my own manner. For 30 years now, in my third life, I have been able to work in peace and pursue my vocation, relying on the creative background that I found and accumulated in Russia.»

In 1978, the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR stripped the artist of his citizenship and the opportunity to return to his homeland. In 2006, the Russian ambassador to France — and later, Minister of Culture — Aleksandr Avdeyev during a special ceremony gave the artist the passport of another country, instead of the lost Soviet one. Rabin immediately transferred his new Russian passport to canvas, according to his already established artistic tradition.

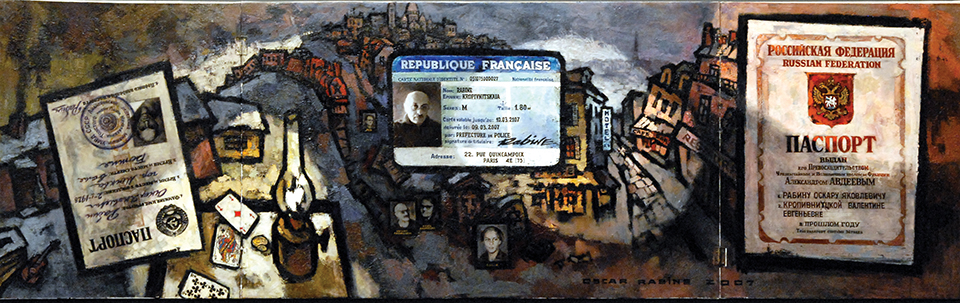

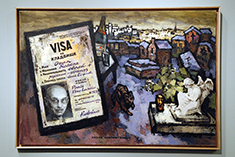

In 1964 he created the first version of the Passport, with the Ethnicity field saying «Latvian (Jewish).» This double entry could not have been permitted in any Soviet document. In 1972, the second version of this work was created for Dina Verni. It featured the field Place of Death, unthinkable for a passport, saying contemplatively, «Under a fence? in Israel?» (the first suggestion is somewhat analogous to the English phrase «in the gutter»). In 1994, after receiving a Russian visa, Rabin created another pictorial document, entitled Visa to Cemetery, complete with a seal of the consular office of the Embassy of USSR, a country that no longer existed. This was a meaningful gesture rather than an accident: at the moment, the homecoming meant a return to the past which had already been parted with, a meeting with something long dead.

The 2006 triptych Three Passports has a markedly different pitch. The left part depicts an inverted — discarded, unnecessary — Soviet passport, the center is an image of the French carte d’identité, and on the right is the new, unfamiliar, painted in warm tones Russian passport, freshly issued, clean and containing exactly 36 pages, as indicated below by the artist. The trip to Russia turned out to be not merely a visit but a return, and it was this passport that made it possible.

In 2006, an exhibition was held at the Personal Collections department of the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, featuring Oscar Rabin’s pieces alongside the art of his wife Valentina Kropivnitskaya and his late son Aleksandr. And two year later Moscow finally saw the complete, official, and victorious return of Rabin the artist. He came to Russia for the opening of an extensive solo exhibition of his works at the Tretyakov Gallery. A major contribution to the organization of this event was made by the U-ART Foundation, created at that time — and in many respects specifically for that occasion — by Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov.

…The life of Oscar Rabin is reflected in his works. His iconography is immediately recognizable and understandable in Russia, both Soviet and modern…

The Manasherovs, art collectors and patrons, met the artist almost by accident. While in Paris, they were invited to visit Rabin’s workshop, located not far from the Pompidou Center. Oscar and his wife Valentina Kropivnitskaya told their life story and showed some works to the visitors, who were tremendously impressed. As the collectors recall, immediately after the meeting they felt a desire to do something meaningful — it seemed wrong to just say goodbye and part ways.

Talking with Oscar «was a powerful incentive to understand the history of art and the Russian avant-garde,» collecting which by this time was already among the pursuits of the Manasherovs. In fact, during this meeting they realized that it was necessary to act in order to «support those who create the present-day history of Russia, who are already inscribed and woven into the history of our culture and yet enjoys undeservedly low popularity in Russia and is inexcusably underrepresented in our museums…» And so was born the concept of the monthly publication Oscar Rabin (2007) and the album Three Lives (2008), to be issued by the opening of Rabin’s retrospective at the Tretyakov. The publications were created in several languages: Russian, English, and French. Over these years Rabin had become significant in Russia as well as abroad, but the main objective, according to Tamaz Manasherov, was to reintroduce the audience to his art at home, reminding everyone that this was an accomplished contemporary artist who changed the course of things and made his impact on the period’s cultural context.

The exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val opened on October 28, 2008–30 years after Rabin left the USSR and ten years before his death in November 2018. These numbers seem to carry hidden meaning — more than just memorable dates, they are milestones marking changes in the country’s cultural life.

At the opening of the artist’s first major exhibition in Russia. Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val, 2008

In December, 2018, Oscar Rabin’s posthumous exhibition opens at the Multimedia Art Museum on Ostozhenka. Of course, this is not a full-fledged retrospective: Rabin’s works are kept in museums and private collections all across the globe, and putting them all together would have been a serious project requiring a long preparation. However, the exhibition presents works that belong to different periods, reflecting the artist’s long and productive career. It is no less important that this first posthumous exhibition is a respectful tribute to the artist’s legacy. The halls displaying Rabin’s works will become a place to gather for everyone who wants to say goodbye, honor the great artist’s memory, and revisit his pieces or discover something new in them. The provides a rare chance to see works from private collections (Iveta and Tamaz Manasherov, Igor Tsukanov, Alexander Kronik, and others). The life of Oscar Rabin is reflected in his works. His iconography is immediately recognizable and understandable in Russia, both Soviet and modern, and his creative style feels intimately familiar and sometimes needs no commentary.

Text: Olga Muromtseva

Photo: personal archive